I tend to have little light-bulb moments in my life that help cement learnings, ideas & theories. They happen quite a bit. I try to write them down in my Evernote if I am out and about, or Tweet about them. They rarely work out of course, but I enjoy the burst of enthusiasm I get from them =)

Last year I tweeted that owning $MSFT versus $IBM was as simple as following the fundamentals. At first it was a bit of a joke because it was so simple, but after building out a few more names, I started to think, “Maybe it is that simple?”.

So I wanted to flesh it out further in a post, and hopefully, run an example like this every once in awhile.

Back Then

Right off the bat, the first thing to think about is would anyone buy Microsoft and/or IBM back in 2011/2012? Well thankfully, both of these companies checked a lot of boxes fundamentally, were in “tech”, and were both in headlines quite a bit (Good and bad).

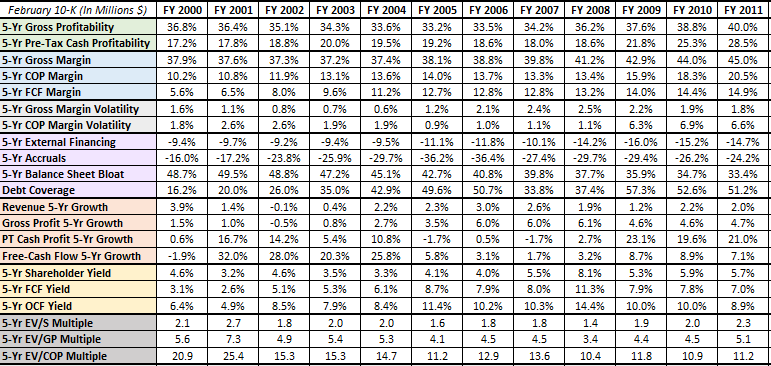

IBM was a bit of a darling back them. Management was being praised left and right. Buffett had just taken a big stake. There was a software tailwind at it’s back. It was sound on a fundamental basis, decent income yield, and was reasonably priced:

Microsoft was sound financially as well. Even more so than IBM which we can see in the metrics below. However, there we’re some poor headlines floating around about Microsoft’s future. Many folks we’re saying Microsoft was “stuck”, management is “inept”, etc.

The Test

Since both looked like decent bets, for different reasons, let’s invest in both and see what happens.

This is where my initial theory started to kick-in and get tested. The whole idea was/is:

What if you simply bought companies in good positions today (Profitable, financially strong, reasonable value in relation to a guesstimate of future growth, and either they had a strong competitive advantage OR were in an industry with noticeable tailwinds) AND then watched the fundamentals of the business every year for hold/sell decisions?

Sounded reasonable. I imagine being sent my annual report as a co-owner, seeing the numbers, listening to the annual call/presentation, and then making a decision to hold or run for the hills =)

So let’s see what happens.

Following Along

Because Microsoft and IBM have different fiscal years, it does not line-up perfectly, but we will use their respective 2011 Fiscal Years as our entry point, and then take a look at our financial reports on an annual basis.

Microsoft releases there 2011 FY results in July 2011 (FY ends June). And despite the poor headlines, things look sound, so we take a position at the start of August 2011. Still growing, sound balance sheet, industry tailwinds, high yield, super “cheap”, etc. This could be a decent bet despite the headlines.

About 6 months later, it’s March 2012 and IBM has just released there 2011 FY results. Pretty sound once again, and at a 7% free-cash flow yield, this could be a nice compliment to the Microsoft position you added last year. Besides, Mr. Buffett stepped in recently =)

Now, the boring part. We simply wait to get our annual updates as shareholders.

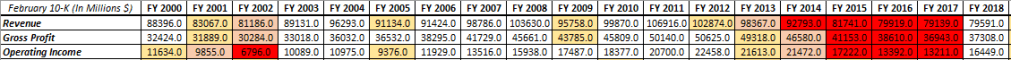

It’s July 2012, and Microsoft releases their Fiscal Year results, and they look good. Some top-line growth, no red-flags, etc. and so we hold. Six months later, and IBM releases their 2012 FY results and things are a little different. There was some top-line rev declines, but margins improved and so lower down on the income statement, things still grew. It’s a “quality” company, and a single year of top-line declines isn’t the biggest deal.

Now it’s July 2013. Microsoft has top-line growth again, margins have compressed a little, but still hard to argue with the results too much. Our original thesis is still in place, so we continue to hold. Six months later, and IBM releases their 2013 FY results. Hmm. Second year in a row of rev declines. And it’s also passing through to lower levels as gross/operating both declined this year as well. This is a bit of a red-flag. If someone said they wanted to sell here, I wouldn’t argue, but then again, this is IBM. Buffett still owns it. It’s still a “quality” company. Let’s give it another year and see how the business does.

Now it’s July 2014. Microsoft, like clockwork, has some growth, fundamentals are still strong, and the thesis is still intact. Six months later, and IBM releases their 2014 FY results. Shit. Third year in a row of rev declines, second year of operating declines. We’re out.

So how does it look. Well, in the 3 years of owning Microsoft, you earned 19.7% p.a, outpacing the S&P. In the 3 years that you owned IBM, you earned -4.3% p.a., underperforming the S&P. You win some, you lose some.

*Spoiler Alert* That trend continued for quite some time (For both companies):

Conclusion

Now this is just one example (I hope to provide others down the road), but it does lead to an interesting question:

Can it be that simple?

Well for starters, the benefit of fishing in a “high quality” universe is very important. Even with 3 years in a row of top-line declines, you we’re still only down ~13% on IBM. If this we’re a “low quality” name, my guess is that figure would be a lot worse. “High-quality” tends to provide an extra year or two of “benefit of the doubt syndrome”.

I also think that because these are both tech names, cyclicality is less of an issue, and so revenue declines, especially a few years in a row, is a great indicator of trouble. For a more cyclical industry, it would be harder to guage solely on income statement growth/declines.

There are some other caveat’s as well, but in the grand scheme of things, I actually think this is not a terrible way to manage a portfolio of high-quality businesses. It focuses on the fundamentals of the business, which is something most investors claim to do anyways…

The major key is that future growth relative to today’s price is the lifeblood of a high-quality company. There is of course no way to know what future growth may be, but it better be something positive.

Lastly, my internal pushback last year was “this is dumb”. In 2021, this is essentially molasses investing. Literally anyone can do this analysis and there is ZERO edge in managing a portfolio this way. And so odds are, it is dumb.

But I would also pose the question of “would most people even have the patience to run a portfolio this way”? Ignoring almost everything outside of annual reports, including stock price in most cases? Fat chance.

So time will tell how dumb of an idea this is, but it is something I will try and practice as best as I can. In a few years, maybe I will be doing another example like this with $INTC and $TSM =)